"Faces of Granizal: Health, Displacement & Diplomacy" is a photographic exhibit that celebrates Colombia's transformation. It is witness to the country's journey towards peace through the perspectives of the people of the rural community of Granizal, giving voice to their experiences as families, neighbors, and displaced individuals. Having been forced to leave everything behind, they labor to recreate homes, roads, markets, sanitation and water systems, health centers, and schools. With limited resources and government assistance and protection, and while living on contested land, they have reestablished infrastructure and a space for peace and prosperity.

Please tap the photos for details about each image.

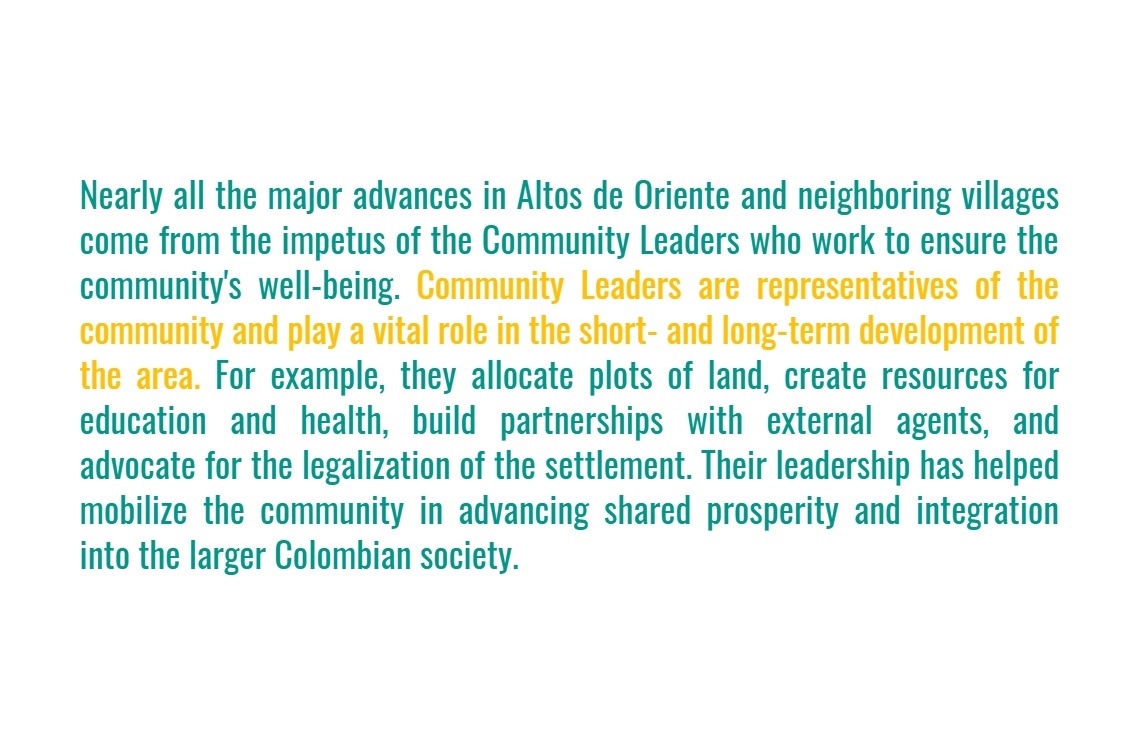

![I was tasked to man the laptop stations to help the people of Altos de Oriente with computer literacy and direct them to health information online… [T]he internet was spotty at best. But even if the internet was fully functional, the first visitor to my station had never created a Word document, saved files on a computer, or knew how to recover or delete files. I live in an environment that necessitates and provides access to learning, resources, and opportunities online. The people of Granizal also live in an environment that requires finding out about their school closings, health warnings, and government advisories – all available online. Access, however, is left to those intermittent times the laptops at the community center are set up and powered. Our visit to Altos de Oriente was a reminder that for whatever tools we make or programs we devise, they are only as great as how well they reach those who need them.

<br>

<br>

NICOLE ESPY

HARVARD UNIVERSITY, STUDENT AMBASSADOR](images/16.jpg)

THE EXHIBIT

The "Faces of Granizal" exhibit first appeared at the Museum of Modern Art in Medellin, Colombia in december 2016 and convened members of local governments, multilateral organizations, academia, the private and non-profit sectors, as well as the media.

After 52 years of armed conflict, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) signed a historic peace agreement and permanent ceasefire, marking the end of one of the world's longest running wars of modern times. The conflict leaves behind a human toll of nearly 200,000 civilian casualties, 25,000 missing, and more than 6,000,000 displaced persons.

At this critical juncture--the dawn of post-conflict Colombia--an opportunity exists for Colombia to redefine its global narrative and for the international community to deepen its engagement with the people of Colombia.

The Open Hands Initiative, with its mission to create greater understanding and goodwill among nations, responded to this momentous shift by creating platforms for ordinary Americans and Colombians to connect. We invite you to join us in looking beyond limiting narratives to discover the Colombian reality now.

Colombia is an upper-middle income country and a leading economy in the region. It is home to highly innovative and progressive cities; and its creative urban design, impressive track record on healthcare, and leadership in environmental stewardship is globally recognized and admired.

Altos de Oriente is a living example of an internally displaced community forced to live in a makeshift settlement, bringing creativity, diligence, and intelligence to their fight to transform their reality. Crowning the mountainsides that overlook the urban meccas of Medellin and Bello, Altos de Oriente stands as testimony to the power of the human spirit.

Colombia's internally displaced population is the largest in the world, second to Syria. Globally, armed conflict has forcibly displaced more than 65 million people--one in every 113 individuals is a refugee, an asylum-seeker, or internally displaced. It is our hope that the experience of the community of Altos de Oriente provides valuable lessons for integrating and supporting displaced populations worldwide.

ABOUT GRANIZAL

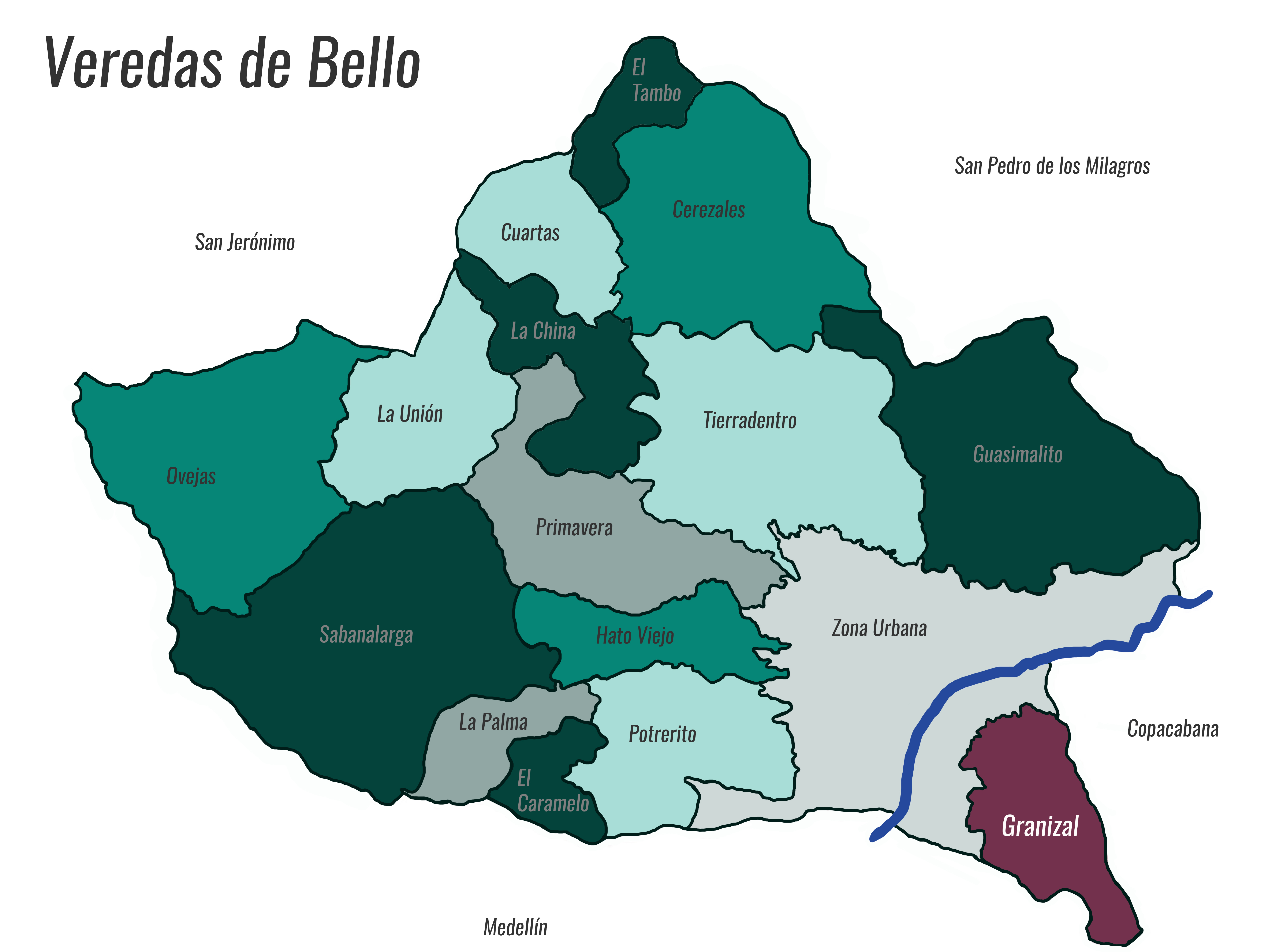

Granizal is the second largest informal settlement of internally displaced persons (IDPs) located within the department of Antioquia, in the municipality of Bello, in northwestern Colombia. Granizal was founded in 1995 and is home to more than 22,000 IDPs, of which 2,300 live in Altos de Oriente.

Granizal is considered one of the poorest settlements in Colombia with 80% of the population living in poverty or extreme poverty. The needs assessment commonly used in Latin America is called "Necesidades Básicas Insatisfechas". It assesses need based on five criteria: geography, basic public services, domestic space, school attendance, and economic dependence.

The community lacks access to electricity, a sewage system, and potable water. The majority of the homes are singled roomed with dirt floors and a makeshift toilet.

There are few public spaces, save for a single primary school and a single community center. The school operates in shifts to accommodate the more than 200 students of various grades. The community center serves as meeting hall, health clinic, and learning center.

Nearly 50% of the community has been displaced for more than 3-5 years. Another 17% has been displaced for 6-8 years. Community members largely hail from Antioquia, with less than 10% coming from outside the department. Altos de Oriente is a relatively young community with about half of the population under the age of 19.

Despite the difficulties endured, the community is determined to build a brighter future for themselves and their country. Members have formed leadership committees to address challenges to infrastructure, land rights, education, healthcare, food security, and employment. Where there was once just empty lots and rule by guerilla forces, there is now an organized settlement moving towards greater integration and a commitment to peace, rule of law, and prosperity for all.

POST-CONFLICT COLOMBIA & PUBLIC HEALTH PROJECT

Open Hands Initiative, in partnership with Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and the University of Antioquia Faculty of Medicine, conducted a three-week academic and health diplomacy exchange in January 2016. The Project investigated and developed practical solutions to public health issues affecting displaced populations. Faculty and students worked in partnership with Altos de Oriente leadership to host a health fair benefiting the community and develop public health interventions on issues identified and prioritized by the community. A subsequent briefing report was shared with members of the Colombian and U.S. governments, the private sector, and civil society, bringing these issues to the forefront and shedding light on ways to aid the community's development and progress.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Kelly Fitzsimmons is a U.S.-based photographer, specializing in fine art and documentary photography. A visual storyteller with a compassion for perspective, Kelly's work spans the globe. Her work has been published in Forbes and is currently on display in Boston.

"For more than 25 years, my art has explored themes of innocence, hope, family relationships, curiosity, coming of age, friendship, and the joys and challenges of the pursuit of independence. Most of that time has been spent making heirloom portraits of children and families, striving to capture timeless images that transcend trends and fads.

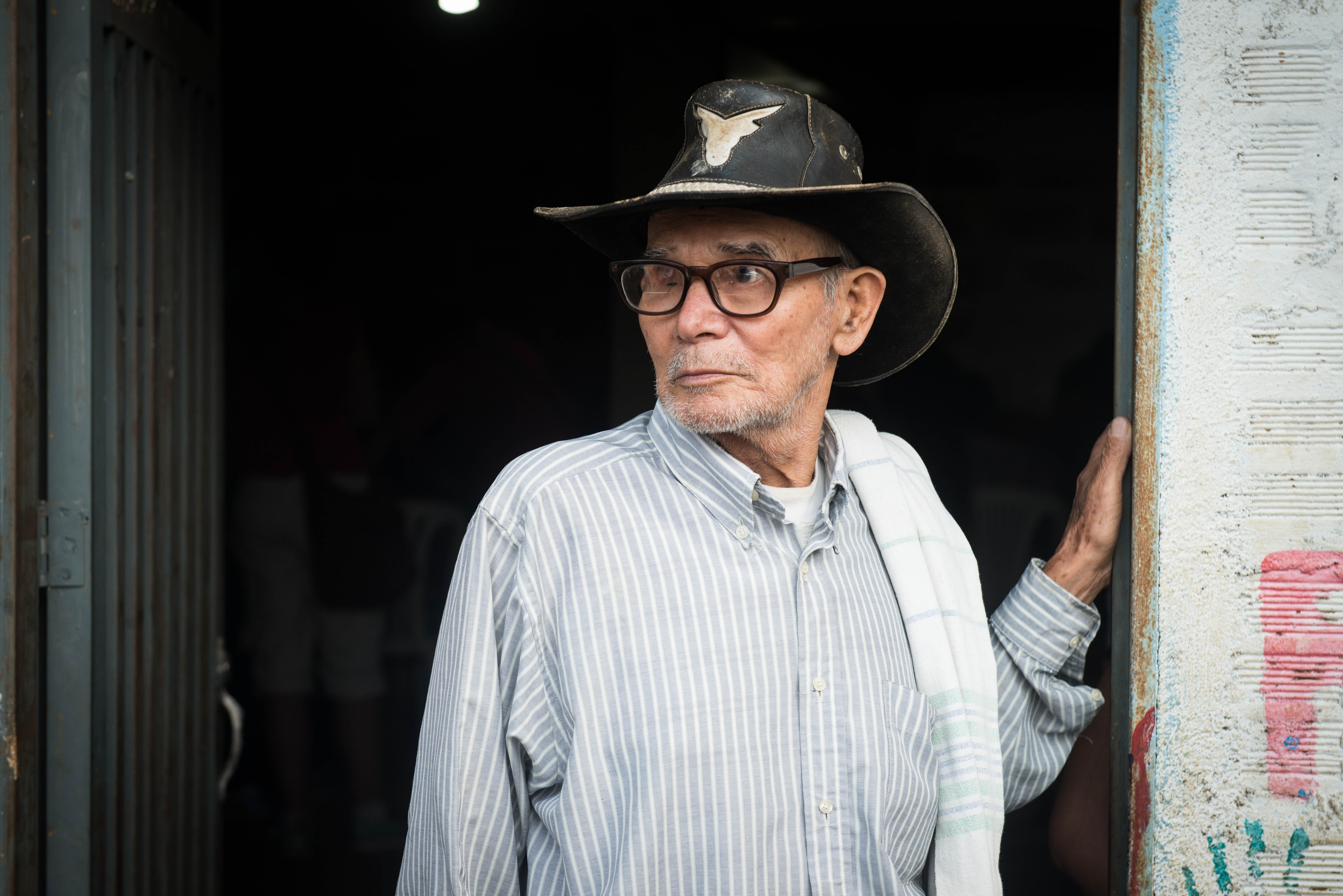

"In photographing the community of Granizal, I was keenly aware of the universality of the themes outlined above. Despite the dramatically different living conditions and the tragic history of violence and displacement, commonalities persisted. Through the lens, I saw unwavering hope and resilience in both the children and adults. From the innocence of toddlers - faces smeared with chocolate - to the aloof, often haunting look of the adolescent teens establishing their identities within a community riddled with poverty and scarce resources.

"By combining both portraiture and documentary photography, I hope to share a glimpse into the heart of the Granizal community and honor its people. I want to highlight the incredible humanitarian efforts of the Open Hands Initiative, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, and University of Antioquia teams. Through these images, I hope the viewer can engage in the struggle and challenge, to see the hope and opportunity to work with equal determination to find solutions to improve health and offer the options to lead productive lives and build a thriving community."

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHS

The photographs were taken using a Nikon D810 camera and 20-70 mm and 70-200 lenses. They feature various landscapes of Granizal, the community members of Altos de Oriente, and the faculty and students who participated in the Post-Conflict and Public Health Project. All photographs were taken in January 2016.

SPECIAL THANKS

This exhibit is made possible by the Open Hands Initiative, the University of Antioquia School of Medicine, the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University. We are thankful for the generosity of Eric Luden and Digital Silver Imaging, and for the expertise of Kelly Fitzsimmons, Sybylla Smith, and Gary Knight. Special thanks to Dr. Jaime Gomez, Diana Alvarez, and all the faculty and students who participated in the Post-Conflict Colombia and Public Health Project. We express our deepest gratitude to the Altos de Oriente community, whom the exhibit honors.